Medieval Ages and the first settlers

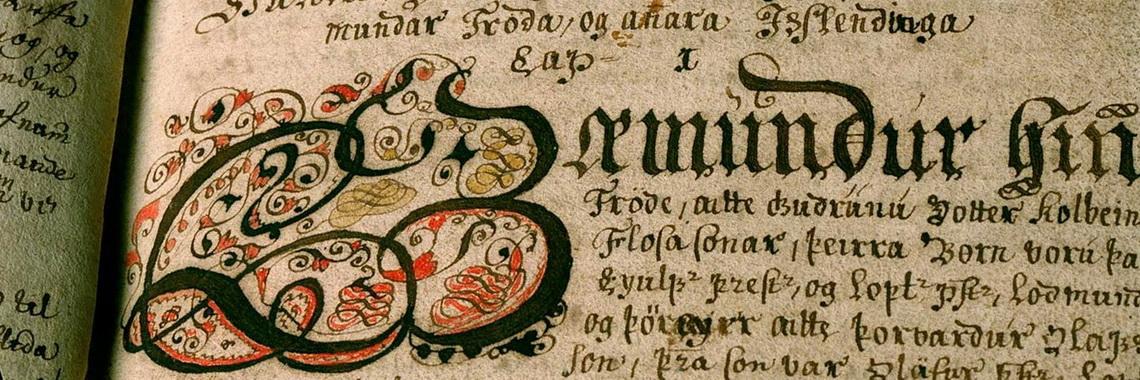

We know about Icelandic history, and the first settlers go back mainly to the Landnamabok (Book of Settlements), the medieval manuscript telling the story about the discovery and settlement of Iceland by Norwegians in the 9th and 10th centuries. The chronicle points to the Irish monks as the island’s first inhabitants. However, Icelandic monks soon left the island due to their dislike of the “northern pagans.”

Ingolfur Arnarson is considered the first permanent settler of Iceland, who arrived on the island with his wife Hallveig and blood brother Hjörleifr and his entourage. In 874, Ingolfur founded Reykjavik, where he settled with his family. Over the next several decades, many Norwegian chiefs followed Ingolfur to escape the oppressive King of Norway Harald, and after about 60 years, they settled most of Iceland’s arable lands. As the population grew and settlements formed, it took a general legislature, the Althingi, created in 930. The ruling chiefs established the Althingi, and the general assembly was considered the oldest national parliament.

It is believed that before the settlement of Iceland, almost a third of Iceland was covered with natural birch forests. The first generations depleted these forest reserves of settlers who used the material to build ships, houses, and farms. Iceland is believed to have been deforested mainly within one century. Until the 14th century, settlers built traditional long Viking houses. Later, due to a shortage of timber, Icelanders continued building turf houses.

The locals needed to trade with the outside world to keep Iceland alive. They usually carried out the trade on short routes to neighboring Scandinavia and Europe. Since Icelandic merchants were mainly farmers, they could not spend too much time away from their settlements.

The first settlers were pagans, following the tradition of their ancestors in Scandinavia. However, when Olaf Tryggvason ascended the throne of Norway in 995 AD, he decided to focus his efforts on converting those under his rule. After several unsuccessful attempts at confession in 999, Olaf closed all trade routes to Iceland, preventing Icelandic merchant ships from entering Norwegian ports. To avoid civil war between pagans and Christians, the Icelandic leaders decided to adopt a new faith; however, pagan worship was still allowed in seclusion. Later, when the church gained complete control in Iceland, all pagan customs were banned.

In the 13th century, when the formation of a nation took place in the country, and the locals identified themselves as Icelanders, there was a civil war. Beginning in 1220, conflicts between the clans were primarily due to the demand for Iceland’s submission to the King of Norway. This period of conflict is called the Sturlung era, after a powerful family in Iceland.

Snorri Sturluson was the chieftain of the Sturlung clan and a vassal of the Norwegian king, like his nephew Sturla Sigvatsson. While Snorri is better known as the writer of the sagas, Sturla made a name for himself by aggressively fighting rival clans that refused to obey the Norse monarch. This culminated in the Battle of Orlygsstadir, the largest known battle in Icelandic history, where Sturla was defeated.

However, in the following years, clashes continued, the Norse king promoted his influence, and finally, in 1262, Gamli sáttmáli (“Old Testament”) was signed. This agreement ended the Icelandic Commonwealth, and the island became a vassal of the Kingdom of Norway. A century later, in 1380, after the unification of Denmark and Norway, Iceland was ceded to the Danes. Danish king Christian III imposed Lutheranism on the Icelanders, and to this day, most religious Icelanders remain Lutherans.

A catastrophic disaster struck Iceland due to the violent eruption of the Laki volcano in the late 18th century (1783-1784), which killed about 10,000, or 20% of the country’s population. The eruption destroyed almost all livestock, causing a famine that claimed most of the lives. When famine struck and the weather began to change on its own, the social order in Iceland collapsed, and looting became common. Besides the prevailing hunger, many died either from extreme heat or from poisonous gases filling the air. The eruption had widespread effects outside Iceland, reaching as far away as North America, Africa, and Europe.

The modern Icelandic history

A new page of Icelandic history was opened when Iceland became a republic on June 17, 1944. When people held a referendum in the country, most Icelanders voted for independence from Denmark. This vote came just four years after the German army occupied Denmark, and Iceland found itself in a neutral and rather precarious position before its illegal occupation.

To strengthen control of the North Atlantic, Britain sent troops to Iceland. To the relief of both sides, the occupation took place without resistance. Canadian and American forces later joined the British forces. During the war years, the influence of British and Canadian soldiers in Iceland faded into the background in favor of the US armed forces. The presence of British and American troops in Iceland has had a lasting impact on the country. Engineering projects initiated by the occupying parties, especially the construction of the Reykjavik airport, provided jobs for many Icelanders. In addition, the Icelanders had a source of income by exporting fish to the United Kingdom.

Despite Iceland’s national independence, the Americans maintained a presence in the country long after the war. The transfer of control of Keflavik Airport to the Icelandic Defense Forces occurred in 1951, although the US Navy retained Keflavik Naval Air Base until 2006. Under the 1951 NATO Defense Treaty, the United States is responsible for defending Iceland indefinitely.

In the second half of the twentieth century, unemployment was low, the industry flourished, and life in Iceland was good for the most part. Iceland became one of the founding members of NATO in 1949, whereas just a year earlier, the country had begun receiving Marshall assistance from the United States.

The next decade of significant interest in Iceland is the eighties. In 1986, a summit meeting of US President Ronald Reagan and Secretary-General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev on nuclear disarmament was held in Reykjavik. This meeting was not a success, but it marked the beginning of the resolution of strategic issues next year, marking the end of the Cold War.

In 1989, Vigdis Finnbogadottir became the President of Iceland and the world’s first democratically elected female head of state. In the 1990s, the Independence Party began a radical reform of the Icelandic economy. As with most significant changes, it took some time to acclimate, but after a short recession, the economy grew rapidly and rapidly again. Iceland’s economy has diversified its industries to not depend on fishing. Iceland joined the European Economic Area in 1994, thus strengthening its position in the international financial arena. Icelanders saw banking as their new way of doing business for a short time, although it turned out to be a short-lived and reckless dream after the 2008-2011 financial crisis.

The eyes of the whole world were already turned to Iceland in 2010, after the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which threw out a cloud of ash, which caused a stop of air traffic over Europe for about a week. After this eruption, interest in traveling to Iceland began to grow steadily. It was then that various agencies in Iceland, including the government and the tourism board, rallied around the idea of making the country a must-see destination. With the island’s healthy economy and natural resources, Icelanders look forward to a bright future. In the meantime, let’s keep our fingers crossed so that no volcanic eruption can prevent this.